| Interview John E. Abele, Part III |

||

| |

|

|

| This

week we continue our interview with John E. Abele, Founder Chairman

of Boston Scientific Corporation. Mr. Abele began his involvement

with the field of minimally invasive medicine over three decades ago.

Today Boston Scientific Corporation is a worldwide leader in the manufacturing

of devices for interventional cardiology and radiology. |

|

|

|

Access previously posted interviews. |

||

| Q: You mentioned that in the beginning a community of developers formed around Gruentzig. How did this community get started? | ||

|

|

Abele:

In November of 1977, at the American Heart, he presented his first

human case. It was kind of interesting because that case had been

done only a month or two before. There was a standing room only audience

and one of the few times Iíve been in any scientific publication when,

after he showed his coronary and the cine of it, the audience stood

up and gave him a standing ovation. Obviously tremendous recognition

of this event. |

|

| That

lead to an avalanche of people, this is Ď77 now, going over and visiting

him in Zurich. These were sort of one at a time cases. But the difficulty

was, he was kind of a lowly person in the hospital and having visitors

come to the hospital all the time and crowd the cath lab was not looked

upon favorably by his bosses. So he had sort of run out of his favors

that he could ask, and the solution was, "why donít I invite them

all here at once?" That was the origin of the first course. |

||

| I

guess there were two or three courses in Switzerland before he came

to the U.S. I donít remember the exact number, but the people who

went to those courses sort of count themselves among the cognoscenti

of the origins of angioplasty. |

Attendees to the 1980 Zurich Course |

|

After the Course: a Party and Torchlight Mountain March |

And

in each course he created great fellowship among the attendees. They

would go out and have their dinners and he would tend to do something

very personal in nature, rather than what one might see now of going

out to restaurants every night. In one of the most famous incidents,

they had the trip up the mountain. |

|

| And

the bonding obviously, as a result, was much stronger. There were

both cardiologists and radiologists and even some surgeons who attended

those courses. So it was a cross-fertilization as well as a bonding

within the cardiology fraternity. Q: Was the creation of this community intentional, premeditated, on the part of Andreas Gruentzig? Abele: Yes. He felt that, if he was going to be successful, he had to have broad appreciation, not only for the procedure, but for the process by which it was developed. And exposing all the warts, as well as the successes along the way, was the best way to do that. So, although operating theaters had existed for 100 years in which surgeons would watch the master at work, this was a very interesting spin-off of that, in which you had the live television and you had critics who were able to comment real time on what was going on in the procedure. |

||

| With

the master, you know, you had to be careful about asking questions

that questioned the skill or the integrity of the master. Gruentzig

invited criticism, he invited questions and, because

of his skill as a communicator and an educator, it was, you know,

just a powerful experience for the audience. |

discussion during an early course (1980) |

|

| So

he introduced not only angioplasty, but really the effective live

demonstration course, which has migrated not only into other areas

of cardiology, but really throughout medicine. |

||

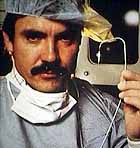

early balloon catheter |

Q:

How did Gruentzig initially view the technique of PTCA? Abele: He made no claims that this was going to be a panacea. He said he envisioned it being maybe suitable for five or ten percent of all patients. And as he developed the technique, and as others developed the technique, yes! The percentage increased. But he did it, stage by stage, rather than techniques that got involved with venture capital, for example, where they start out by saying, "This is a billion dollar business!", and somehow working up to that point. |

|

| Again,

I think, the fact that his commercial connection was more of a modest

one. He had a relationship with Schneider. But he would choose to

go slow and to limit the circulation of the product ó I mean that

was unheard of in any development ó so that he could control it and

teach people. The idea of requiring that everybody who used the product

had to have some counseling or education by him was also rather unique. |

||

| Q:

Having known him before the technique became famous, what would you

say were his prime motivations? Abele: Iíd be guessing here, but I know when my wife and I visited him in Zurich in Ď75, he lived in a very Spartan way, and appeared to feel strongly that this was an appropriate way to live. I would use the world "socialist", if I would go that far. |

|

|

| When

he visited us in the States, he stayed in our house, and he criticized

me for using paper cups (and probably quite correctly, but when you

have a lot of kids, you know...). He would not use the dishwasher,

he didnít have a dishwasher, heíd just rinse them out in the sink,

and that was the minimum amount of water. So Iím extrapolating a bit

here, but I think he was motivated by discoveries for the benefit

of mankind. When you listen to him describe the value of the technique he was using, he was a very personally compassionate person. He did treat patients, not vessels. I think thatís something that sometimes is lost on modern day cardiologists. Q: Could you expand on that ó the idea of treating patients, not vessels? Abele: You have to say, "Now what is the difference to the patient between the way in which [Gruentzig] was treating them and the way in which they would have been treated before?" Now letís say the treatment before is an operation. The difference, a significant one, is itís much less invasive. |

||

talks to an awake patient during PTCA |

But

perhaps more important is that the patient is awake! So the patient

is in fact a partner, or can be, depending on the physician, in his

own, or her own treatment. Iíve always felt that thatís part of the

holistic nature of successful therapy. Unless you get the patient

in on the bargain, youíre not going to get the result that you hoped

for. |

|

| I

think youíre seeing more and more of that in todayís medical environment:

the interest in alternative medicine, the interest in people understanding

their own well-being, the diseases that they may have, the access

to the Internet now. The interest in medicine is just exploding and people are taking more responsibility and interest in their own health ó both the well-being side of it and, if they have a disease, understanding it so they can treat it as a partner with the physician, as opposed to the "leave the driving to us" philosophy that has existed in the past. |

with a patient |

|

|

Paret

IV: John Abele's interview concludes with some observations on Gruentzig's

legacy and its meaning for the world of medicine today. |

||

| |

||

|

Angioplasty.Org Home ē PatientCenter send comments & suggestions

to "info at angioplasty dot org" |

||