![]()

<< To Homepage >>

<<Archives>>

April 2010 Archives:

April 27, 2010 -- 7:05pm EDT See One, Score One for Stents

An angiogram doesn't show the cardiologist much about the shape, distribution, or composition of the atherosclerotic plaque: it mainly shows where it is and approximately how long it is. But, seeing inside the artery, the cardiologist is able to discern, for example in the image above, that the plaque is eccentric, all on one side, or perhaps it's ragged or sitting next to calcified deposits. Putting a balloon in and expanding it may push the calcified plaque through the arterial wall, causing a dissection, or the eccentric nature of the lesion may impede the balloon from fully expanding, leaving a less-than-optimal result. Back in the early days of angioplasty, I watched cardiologists as they saw post-balloon angioplasty images from a very early intravascular device: the angioscope -- literally a camera on a catheter. These were among the first cardiologists to ever expand a balloon inside a human coronary artery...and they were shocked. I remember Dr. Richard Myler exclaiming, "My God, it looks like a bomb went off in there!" Indeed, it looked pretty raggedy -- the balloon dilated the artery alright, but the plaque split up during the balloon expansion in a very messy fashion: there was fatty plaque hanging off the sides of the vessel wall and the whole picture showed something definitely not smooth. This was one reason that plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) had a 30-40% restenosis rate. When stents were invented, cardiologists now had a cage, a scaffold, to push this tissue back against the vessel wall and pin it there. But still, if the plaque were hard, uneven, etc. the stent would not sit quite perfectly, and restensosis or even thrombosis (blood clots) might occur. Enter lesion-specific strategy -- you look at the plaque characteristics and pick the right tool for the job. You have to have an intravascular imaging system to "see one" -- that would be IVUS -- and then, if you saw that the plaque was complex or atypical, you'd need a tool to safely break it up -- and that (in some cases) would be the AngioSculpt® Balloon Catheter. As you can see in the animation below, the nitinol "ribs" on the balloon act as a scoring device. We all know you can't break a piece of glass along a line, but if you score it part-way first with a glass cutter, you can break it perfectly straight. And so, if the IVUS image shows an irregular complex lesion, what's known as a type-C, you might want to pre-treat the plaque, so that when you do expand the stent inside, the plaque expands easily, atraumatically, and smoothly -- seating the stent cozily, right up against the vessel wall.

That's the basic concept of the AngioSculpt balloon, manufactured by AngioScore, Inc. And today Volcano Corporation (Nasdaq: VOLC), makers of IVUS equipment, announced that they are now the distributors for Japan of the AngioSculpt line. It's a perfect fit because it marries distribution of the technology that allows you to "see one" with the technology that allows you to "score one" -- making outcomes for patients better. « permalink » « send comment » « back to top »

April 17, 2010 -- 11:30pm EDT Heart Attack and Angioplasty: A Public

Education Challenge But what's most important to me about the study is that while the fully-insured patients were more likely to seek out timely treatment, almost 40% of them delayed going to the hospital for more than six hours -- leaving them with a legacy of damaged heart muscle and future heart failure -- needlessly! Obviously, it's not just money keeping heart attack victims away from the ER. Do you know someone who's had the symptoms of an MI and has tried to make-believe they're experiencing something else: a pulled muscle? an acid stomach? To be trite: denial -- not just a river in Egypt. You get the idea.... Of course, many times the onset of a heart attack does not present as the classic crushing chest syndrome, where you grip the heart and say, a la Redd Foxx, "Call 911! I'm havin' the Big One!" Sometimes the symptoms are subtle, like my relative who was sitting on our couch after dinner one night, complaining of indigestion. It wasn't. It was a heart attack. Unluckily for him, it was 1972. It would be five years before the first angioplasty would be done and another three before Geoffrey Hartzler decided to open up his patient's artery with a balloon in the midst of an acute infarction, miraculously stopping the heart attack in its tracks! I wrote recently about the evolution in the treatment of heart attack since the days of Eisenhower. I remember those days, as a kid in upstate New York, walking home from school on a sunny weekday afternoon and seeing at least four of my friends' fathers, sitting on their front porches in their rocking chairs. I always wondered why these fathers didn't go to work during the day like mine did. Heart disease was why. Four fathers, just on my one block, had been struck down by a heart attack. They could no longer work, could barely drive a car and they all died in their 50's. So perhaps this is what we all visualize when we think "heart attack" -- it's an upheaval, a catastrophic end to a life of work and play, sitting on the front porch and waiting.... Perhaps this is why people who suspect they may be having a heart attack don't want to go to the hospital -- it's not going to make a difference -- I'm done for already. Except that's not the case at all today. As angioplasty pioneer Dr. William O'Neill relates in the video clip below, angioplasty has radically changed all of this and has "taken the dread factor out of heart attacks." In our interview, he actually characterized the experience of having a heart attack treated today as "not so bad, perhaps a little more than a cold." An over (or under?) statement to be sure, but maybe, if more people understood this, there would not be so many staying away from the ER. The ACC has done a great job with its "door-to-balloon" initiative. But that's what occurs inside the hospital doors. What needs to happen now is some significant public education to get those patients knocking on the door outside for help!!

« permalink » « send comment » « back to top »

April 11, 2010 -- 9:10pm EDT "I'm a Dead Man"

So the anecdotal experience of feeling the emotions of this patient very much informs my interpretation of the two studies published today in the New England Journal of Medicine. There are charts and graphs and tables, and 30-day outcomes and five-year outcomes...but I remember the man who would not be sitting in from of me were it not for this ingenious metal cage covered in fabric. « permalink » « send comment » « back to top »

April 10, 2010 -- 5:00pm EDT Angiogram Not Angioplasty For Holbrooke In fact, the procedure was an angiogram. Two letters and 10-20 minutes shorter -- but a world of difference. Having reports of chest pains, Holbrooke's doctor ordered a diagnostic test, also known as a cardiac catheterization: a catheter is threaded through the femoral (groin) artery or the radial (wrist) artery to the coronary arteries surrounding the heart. A special dye is injected and, under X-ray fluoroscopy, any blockages can be seen. In Holbrooke's case, no significant narrowings were found and he has, in fact, been cleared for his trip. Had a major blockage been found, an angioplasty might have been done: guide wires rapidly would have been exchanged and a balloon with a stent on it would have been threaded to the blockage, inflated for a short time, deflated and withdrawn. The stent would remain as a scaffold, holding the artery open. Only 20 extra minutes, maybe 10. This is why many angiograms that show blockages are converted into therapeutic procedures, angioplasties, right on the table -- because it's easy and fast to add it on. ("And while we're at it, we'll change the oil...", a cardiologist friend of mine used to quip.) Of course, this instant conversion, also called "ad hoc angioplasty", has come under some questioning since recent studies, notably FAME, have shown that just because you can see the blockage doesn't mean you need to open the blockage up. But that's another story. This story ended well for Ambassador Holbrooke. And by the way BusinessWeek -- clogged heart valves? |

When

the task at hand is performing angioplasty and placing a stent,

the phrase being used more and more is "lesion-specific strategy".

What does this mean? Well, looking at the angiogram on the left,

you can certainly see the lesion, or blockage...or rather, you

can see where the narrowing caused by the blockage is. You can't

actually "see" the lesion itself unless, of course, you

could get inside the artery with a camera.

When

the task at hand is performing angioplasty and placing a stent,

the phrase being used more and more is "lesion-specific strategy".

What does this mean? Well, looking at the angiogram on the left,

you can certainly see the lesion, or blockage...or rather, you

can see where the narrowing caused by the blockage is. You can't

actually "see" the lesion itself unless, of course, you

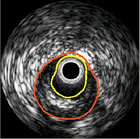

could get inside the artery with a camera. That's

basically what intravascular imaging does: a device is threaded through

the arterial system, along a guide wire (the same wire that the balloon

and/or stent will track) and, using ultrasound or lasers or near-infrared

energy, it will image the inside of the artery. The most commonly-used

system is called IVUS (IntraVascular UltraSound).

That's

basically what intravascular imaging does: a device is threaded through

the arterial system, along a guide wire (the same wire that the balloon

and/or stent will track) and, using ultrasound or lasers or near-infrared

energy, it will image the inside of the artery. The most commonly-used

system is called IVUS (IntraVascular UltraSound). This

week's JAMA contains

This

week's JAMA contains

A

minor print error, but not for Richard Holbrooke, the U.S. special

envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan. On Wednesday

A

minor print error, but not for Richard Holbrooke, the U.S. special

envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan. On Wednesday