|

|

|

|

|

|

Angiograms: Shadow Images

The images that we see form a construct in our brains of what may

be reality. For half-a-century, the two-dimensional shadow images

of the coronary arteries,

as served up by the "gold standard" of selective coronary angiography,

have informed cardiologists as to what a stenosis is, how severe it is, where

it stops, starts, what it's composed of and, perhaps, how to best treat it. |

|

But newer intravascular imaging modalities have challenged those

black-and-white renderings, and have offered a more accurate image

of what in fact is going on inside the coronary arteries: accuracy

that has resulted in better outcomes for patients and potentially

lower healthcare costs due to less repeat procedures.

The diagrams to the right show an actual

LAD

blockage and an artist's rendition of the same..

Certainly that fluoroscopic shadow image can be measured, comparing

the narrowed area to what looks like the full size of the

artery

before and after the blockage. And

it can be pronounced an 80% or 90% stenosis. This is, however,

a measurement of the image, not necessarily of the arterial blockage

itself, because the angiogram

is, in essence, a two-dimensional "shadow image" of the

artery.

|

|

Coronary narrowing,

as

seen on angiogram (top)

and artist's rendition

of the same |

|

For example, what if this blockage, or

stenosis, were eccentric? What if viewing this artery from a different

angle showed less (or more) narrowing because the blockage

was oval-shaped in the extreme? What if the disease actually spanned

a greater length than the angiogram showed? What if the entire

segment of the artery were diseased and the native arterial

diameter was actually wider than the angiogram showed?

These are all situations

in which the angiogram may or may not show the accurate picture

of what is going on inside the artery. And misjudging the diameter

and length of the blockage may lead, for example, to undersizing

a coronary stent to be placed. More on this later....

|

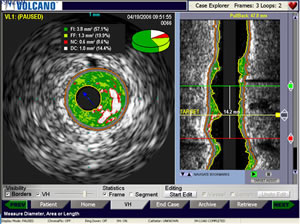

Intravascular

of artery (left) and

reconstruction (right) |

|

IVUS: Imaging

the Artery from the Inside Out

Enter intravascular imaging and guidance, in the

form of intravascular ultrasound, or

IVUS. An ultrasound imaging device is quickly threaded over a wire

and through the catheter that injected dye for the angiogram. A special

"ultrasound camera" is able to see through the plaque and

determine where

the

actual native wall of the artery would be (if the plaque were not there).

This same "camera" also images the plaque itself --

and with some systems, such as VH-IVUS, is able to characterize

the plaque (hard,

soft, calcified,

lipid-rich, etc.). The IVUS imaging device is then "pulled back"

through the entire arterial segment, generating a rapid series

of cross-sectional images which are quickly processed into a longitudinal

reconstruction of the artery.

|

|

As can be seen in the above image, the

IVUS reconstruction is not a shadow image, but an extremely precise

and measurable roadmap to the artery. The software quickly measures

the

diameter and length of the blockage and tells the cardiologist exactly

the diameter and length of the stent he will need to optimally open

this blockage.

Which brings us to the "IVUS State of Mind"....

|

|

IVUS First Identified a Major Problem with Stents

At the beginning

of the stent era, problems began to arise with excessive restenosis

(re-blocking of the artery) and stent thrombosis (blood clotting

inside or around the area of the stent). IVUS was, at that time,

a very new imaging modality. And one of its proponens was Milan-based

Dr. Antonio Colombo. He used IVUS imaging before and after stenting

and looked at patients where the results of the stent had been poor.

And what Colombo found has changed the way stents have been deployed

ever since.

|

|

Antonio Colombo,

MD |

|

When stents first came into widespread

use, cardiologists understandably were overly cautious with this

new technology.

They

were afraid to

expand the stent too far

for fear of over-expanding and tearing the artery.

But Colombo's

IVUS images showed that many, if not most, stents were being underexpanded,

underdeployed -- that they weren't being fitted snugly against

the arterial wall. The result of this underexpansion was that the

spaces

between the stent and artery wall became areas susceptible to platelets

collecting and forming clots, or tissue growing and causing restenosis.

Like an ill-fitting door or window, the space around a too-small

stent was causing the exact problem it was trying to eliminate.

So cardiologists began using high-pressure balloons to expand

the stents fully. And the only true way to measure the exact diameters

and lengths was to use a technology like IVUS. If the cardiologist

knows the precise size of the artery and the blockage, he or she

can size the stent correctly and expand it fully...and safely...without

worrying that the stent is going to overdilate the artery. And

to make sure that the stent is long enough to cover all the disease

(implanting a stent edge in a diseased area is a sure way to cause

reblockage later on).

Just as angiography first gave doctors a way to think visually

about the coronary arteries, intravascular imaging modalities like

IVUS

are now giving cardiologists a new, more complex and more accurate

way to "see" and treat coronary artery disease: an IVUS state of

mind.

In our interview

with Antonio Colombo,

we asked him if he uses IVUS on every single case. His answer

was, as follows:

"Almost all. It depends. In a public hospital sometimes

I am pushed by the schedule, by the patient load, so sometimes

I have

to make

some practical decision. If the lesion is very simple, I

cut short. But still, having used IVUS most of the time,

I have

acquired

what you might call an IVUS background, an IVUS mentality....

So I always think of the vessel as a little bit bigger than

the way it looks. But Ive been working in this field for

more than 25 years, so sometimes I assume that I know...."

|

Shigeru Saito,

MD |

|

Taking an IVUS image adds only

minutes to the procedure and studies show a correspondance between

IVUS use and lower rates of restenosis and thrombosis. Take, for

example, the experience of Japan, where IVUS is completely reimbursed

by insurance and

so is used

in virtually

every PCI. When randomized clinical trials of new

stents are published, the Japanese cohorts always show lower rates

of complications.

So Angioplasty.Org asked Dr. Shigeru Saito, principal

investigator for many of these clinical trials and studies, why

this is the case? Why are the Japanese results always better?

His answer? IVUS!

|

Reported by Burt Cohen, September 24, 2011

|

|

|

|