|

|

|

Dr. Hodgson is an internationally

acclaimed cardiologist who, prior to founding Santé Cardiology,

was the Chief of Academic Cardiology at St. Joseph Hospital

and Medical Center in Phoenix. Previously a faculty member

at the Medical College of Virginia and Case Medical School

in Cleveland, he has devoted much of his career to training

the next generation of physicians. He has served in many

administrative positions and developed four Cardiology Departments.

Dr. Hodgson is a Past President of the SCAI and

a founding member of the SCCT.

He has published over 200 peer reviewed articles, 8 books

or

book

chapters,

holds

two

patents and

developed the TeachIVUS and TeachFFR online

simulation training tools.

Angioplasty recently sat down with Dr. Hodgson to talk about

intravascular technologies. This interview is posted in two

parts:

- Part One discusses intravascular

ultrasound (IVUS) and how it can increase the accuracy

of stent placement, and the role of IVUS in the era of

DES 2.0;

- Part

Two discusses Fractional Flow Reserve

(FFR) with some thoughts on training and recommendations

for patients.

|

|

John

McB. Hodgson, MD

John

McB. Hodgson, MD

Santé Cardiology

Phoenix, Arizona |

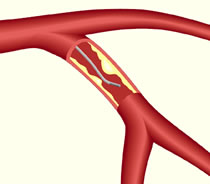

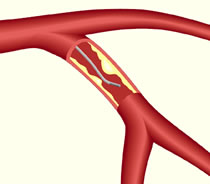

Q: You mentioned FFR, or Fractional

Flow Reserve, which measures any reduction in blood flow across a

section of the coronary artery. Can you explain how it’s done?

FloWire® Doppler

Guide Wire image, courtesy Volcano Corporation |

|

Dr. Hodgson:

FFR uses a guide wire with a pressure

sensor at the

tip.

We do 80% of ours through the diagnostic catheters, so you

don't even need a guiding catheter. It's actually very easy

to do; it takes one to two minutes, tops. We have it set up

on every case. We use, for the most part, intracoronary adenosine

as our hyperemic stimulus, although in rare cases we need to

use intravenous adenosine if there are multiple lesions or

ostial lesions.

The accuracy of the pressure measurement is fantastic.

We typically do three measures for a given lesion, with escalating

doses of adenosine, so that we're sure that we get maximal

hyperemia, and typically the values don't differ

by more than a hundredth, The other nice thing is there's

a

very small

gray zone which, for me, runs between about .75 and .81,

and in that area we use clinical judgment and other things

to decide

what to do. But it's unusual that a patient ends up in that

zone -- usually they're .9 or .6 so the answer's very easy. |

Q: How does measuring the reduced

blood flow affect the patient’s

treatment?

Dr. Hodgson: You have to make a couple of decisions when

you go into the lab, and the most important one is understanding

when not to do something. You need to be sure, that if

you're going to do an interventional procedure, whether it's surgery

or stenting

or balloons, bare metal stents, whatever, you need to be sure that

the patient really needs it.

Not all lesions need a stent. And people

argue “Well, I

have to do something….” Well you are doing something.

You've made a diagnosis, presumably you're going to put that person

on anti-thrombotic agents, agents for their lipids, control their

blood pressure, encourage them to stop smoking, exercise, etc.

So, you are doing something, but it may not be a stent. It's extremely

clear, from both the nuclear data as well as all the FFR data,

that if you do not have ischemia from a lesion, then there is no

benefit to revascularizing it.

Probably the strongest data here is the DEFER

trial (Deferral

Versus Performance of PTCA in Patients Without Documented Ischemia)

where they took cases where, due to blockages seen on the angiogram,

the operator intended to put a stent in. If the FFR was abnormal,

or ischemic, below .75, they went ahead and stented all of those;

the ones that were above .75, they randomized, to go ahead and

implant stents in half and leave the other half medically treated.

Now at 5 year follow-up, the ones who were left to be medically

treated did better in every regard: fewer events, fewer revascularizations,

less angina, etc.

I feel there's a concept out there among many

operators, that every lesion needs a stent, that by

plaque-sealing, we're

going to keep it from causing a problem in the future. But the

data just does not support that, if the lesion is not ischemic.

And I think the COURAGE trial, again, that plays

into that. In my mind, there's just no justification in a stable

patient to stent

a non-ischemic lesion. We're not talking about acute M.I.s, we're

not talking about acute non-Q.M.I.s. We're talking about the run

of the mill patient who somehow gets a false positive nuclear stress

test, or somehow gets on the cath table, and they start stenting

lesions. And there's a lot of that that goes on, unfortunately.

So, step

number 1, make sure that the lesion's really ischemic. If there's

any suspicion, I think that FFR should be done in the lab, to be

sure that you're not stenting a lesion which doesn't need to be

done.

But I do think it's a mistake to tell patients, “Well,

we're not going to do anything”, or “You don't need

anything done”. I think the proper approach is to say “Listen.

You're very lucky at this point. This blockage is not causing any

issues that we need to do anything invasive with, and we're going

to treat it aggressively with medical therapy”. It just depends

on how you present it to the patient. You can tell them that they're

lucky, that they don't have to have a stent. It's a good thing.

Q: For those who want to learn, what are the training opportunities?

Dr. Hodgson:

The bulk of the training opportunities come through courses

and

dinners

and things that are set up by the manufacturers. I think

we've kind of gone past the phase where we offer specific

IVUS training

as part of the big interventional meetings. There are certainly

always IVUS sessions at ACC or SCAI or AHA -- TCT uses a

lot of IVUS. But they don’t do it as part of every case.

We go to the hospital, give a grand rounds or lecture or dinner

meeting or cath conference or something. The most effective ones

in my mind are ones where we stay and work in the lab with people

to help them get through the fear factor of doing it. Another

issue that's critically important is training the techs and nurses

to be facile at using it.

I run 6-8 courses a year; we bring in 20 people. Now we're doing

a lot more dinner meetings, going out to the sites, so we can

get more people there. |

|

Dr. Hodgson

lecturing about IVUS during a session at the annual

TCT meeting |

The truth is we've been struggling for 13 years,

ever since we started the program when Cordis was co-marketing

with Endosonics,

to find a method which gets these guys excited. IVUS for whatever

reason, just never caught on as being something that we have to

do. You know when Rotablator came on everybody wanted to be trained.

And when DVI came out everybody wanted to be trained. When FoxHollow

came out everyone wanted to try it. In the early days, and I mean

early '90s, there was a lot of interest in IVUS and a lot of people

wanted to know about it, but then their interest falls off when

they don't feel that it makes a big difference to them, and it's

an attitude issue at that point.

A lot of younger fellows who've trained at a

place that uses a lot of IVUS come out and can't imagine doing

without it. Other

fellows come out of training and their mentors were less interested

in IVUS, and they come out with no interest in it. So, it's difficult.

The

three things that we learned in the mid '90s were they didn't

believe it improved patient outcomes, and we did a host of trials

in the late '90s to prove that that wasn't true. Second thing

was

they felt it was too hard to interpret, and we've spent a lot

of time and energy improving the interpretation and automating

the

border detection and all that kind of stuff, making the systems

easier to use. And the third thing is they said it was, it took

too much time, it was too difficult to do mechanically. We've

got integrated systems now, we've got very easy to use catheters,

and

that's just not true.

Q: What about the online program,

Teach IVUS – which

is co-sponsored by Volcano Therapeutics and Boston Scientific?

|

|

Dr. Hodgson: I'm biased

since I wrote it. It's a useful tool, sure. The nice thing

about

Teach IVUS and the thing that we do in all of our Teach products

(you know we have Teach CTA and Teach FFR, as well) is that

we give immediate expert feedback. So we require you to draw

or mark or point to or label or do something interactive with

the images, then you get immediate visual feedback as to what

the right answer was, where the drawing should have been, where

the border really was. And then we ask questions, based on

your measurements: “What would you do now?” So we do some sort

of teaching.

It's not about clinical decision making in terms

of cases; it's about “can you interpret these images properly?” And

so I think people can do that, it's non-threatening, you can

do it in your spare time, there's nobody pressuring you. I

think if every tech were to work on that, and a lot of labs

use it that way, then they'd be much more comfortable doing

the border tracing and border correction stuff that they need

to do during a live case. |

Q: What are the implications for patients here? Is this something

they should know about and ask for?

Dr. Hodgson: I think so. I think for the

most part if you ask doctors, “If

you're having a heart attack, do you want angioplasty or thrombolysis?”,

they all say they want angioplasty. If you ask doctors, “you

need a stent in your proximal LAD, do you want them

to use

IVUS or not”, they'll all say yes. So they all know the answer.

The patients, the educated ones will ask about it. I think it's

something that should be talked about. We do have it on the

SCAI web site describes some of these other

ancillary tools. We've toyed with a direct patient advertising

campaign. But I'm not sure how to get the message out to patients,

because it really has to be targeted to people who are likely to

have procedures. This is not a drug they can take, or a new exercise

regimen. FFR and IVUS are only applicable during a cath. So you

have to find the people who are about to get a cath and somehow

educate them.

Q: Angioplasty.Org currently

gets 100,000 visits a month. We’d

like to think we’re helping.

Dr. Hodgson: That's fantastic!

You should certainly encourage the patients to discuss with their

doctors two key things:

- is

this blockage really causing a restriction of blood flow,

or lack of blood flow to the heart, or however you want to

phrase

it, and

if not, I would prefer to continue my medical therapy,

and

- If this blockage needs to have an intervention,

how are

you

going to ensure that the stent, or whatever the intervention

is, is going to be done optimally? Are you going to

use IVUS or FFR

or some other method to be sure that you've done a

good job mechanically?

And those are two questions that

every patient

ought to ask when

they go in. Are you sure I need this and what's

the data, what's the proof, and number two, are you sure you

did a good

job? How

are you documenting your job? If you get a “well

it looks okay to me”, that's not good enough.

For the latest news and information about imaging, visit Angioplasty.Org's Intravascular Ultrasound

Center.

(Return to Part One)

This interview was conducted in February 2008

by Burt Cohen of Angioplasty.Org.

|