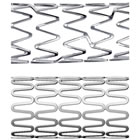

Which stent platform do you think compresses more easily: Boston Scientific’s Element (top) or Medtronic’s Integrity (bottom)?

I first heard concerns about stent deformation, primarily seen in the PROMUS Element stent made by Boston Scientific (NYSE: BSX), during a presentation at a small interventional meeting last summer. The issue was then reported in two journal articles, just prior to the TCT meeting in November, where it became a topic of much attention — although most interventional cardiologists felt that it was nothing like the problem of late stent thrombosis, first seen as a “rare” event in the first generation of drug-eluting stents five years ago.

I reported extensively on longitudinal stent deformation a few weeks ago when Dr. John Ormiston’s article in JACC Interventions was published. Angioplasty.Org’s coverage can be read in the following articles:

- New Boston Scientific Stent Shows Significant Shortening Compared to Other 2nd Generation DES

- Avoiding and Repairing Coronary Stent Distortion

- Stent as Concertina

The Reuters article cites the thinner struts of the new generation of stents as a possible cause. However, it’s not necessarily the thinness of the stent struts but the design and structure of the stent lattice that may be a reason for this vulnerability. For example, the photo at the top of this post compares Boston Scientific’s Element stent design with Medtronic’s new Integrity platform. Which one do you think would be more prone to the so-called “concertina effect”? The Element, in which the peaks and valleys line up and look, well, “squeezable” — or the Integrity, where the peaks oppose each other?

This issue of stent compression was measured in Dr. Ormiston’s study in which he bench-tested seven stents, confirming anecdotal reports that Boston’s Element stent platform was more prone to stent compression (only four of the total are shown in this photo).

This issue of stent compression was measured in Dr. Ormiston’s study in which he bench-tested seven stents, confirming anecdotal reports that Boston’s Element stent platform was more prone to stent compression (only four of the total are shown in this photo).

But it’s not just thinness because Abbott’s XIENCE stent platforms (both the older XIENCE V and newer XIENCE Prime) both fared well, even though they, like the Integrity, boast thinner (and therefore more flexible) struts.

And it gets more complicated because another factor cited in Ormiston’s study was the number of connectors between the strut hoops. Element uses only two, as does Medtronic’s decade-old Driver platform, which also showed a vulnerability to compression, although less than the Element. Abbott’s XIENCE has three and the older CYPHER (the least compressible) has six. So do more connectors equal less compression? Sounds correct, except that Medtronic’s Integrity, which performed very well, has only two connectors. Ormiston posited that this may be due to Integrity’s unique design: it’s fashioned from a single wire (hence the name, Integrity).

So, no news here: the issue of stent performance is a complex engineering design calculation. What is meaningful, as the Reuters article points out, is that Boston’s brand-new design is the basis for its entire product line of new stents. The article quotes Dr. Mark Ricciardi, director of Interventional Cardiology at the University of New Mexico Health Science Center, as saying:

“When there’s a new device like (Promus Element) that’s not a game changer and then you find out there may be issues, you tend not to want to use it.”

If many interventional cardiologists feels the same way, Boston Scientific’s stent division may have some problems, certainly against Abbott’s XIENCE, and even more when Medtronic’s new Resolute drug-eluting stent receives FDA approval, anticipated sometime next year.

Speaking of the FDA, the “news” that prompted the Reuters article was that, when the FDA approved the PROMUS Element last month, it required Boston Scientific to include a caution in its labeling. As previously reported on Angioplasty.Org, the package insert for the PROMUS Element stent devotes Section 6.3 (page 4) to this issue, and the section leads off with this warning:

“Crossing a newly deployed PROMUS Element™ stent with a second device, such as a balloon catheter, stent system or IVUS catheter, can lead to the second device becoming caught on the PROMUS Element stent.”

Dr. Cindy Grines of Detroit Medical Center and editor of the Journal of Interventional Cardiology and author of one of the first reports of the issue of stent compression, is also quoted in the Reuters piece:

“It’s good there’s a warning, but it needs to be advertised to the interventional cardiology community. We’re a high volume center and I haven’t heard about it,” she said, adding that having it buried in a label is not useful. “Nobody reads the labels.”

Again, longitudinal stent deformation has been reported only in a small percentage of procedures. And, if recognized, it usually can be repaired on the spot. But we would guess that the executives at Boston Scientific are definitely keeping an eye on whether the number of these reports increases, as a result of “reading the label”.